Selected Nonfiction

The Eternal Country: How an Epic Poem Came to Define an African Nation State

This is about an old poem and an old country, Mali, which is today mired in civil war. In November 2011, weeks before the war started, I trekked from Mali into neighboring Guinea to visit a village on the Sankarani River where legend has it a great sorcerer came to power some eight hundred years ago. (READ THE ESSAY in POETRY INTERNATIONAL)

This is about an old poem and an old country, Mali, which is today mired in civil war. In November 2011, weeks before the war started, I trekked from Mali into neighboring Guinea to visit a village on the Sankarani River where legend has it a great sorcerer came to power some eight hundred years ago. (READ THE ESSAY in POETRY INTERNATIONAL)

Poetry International, 2019

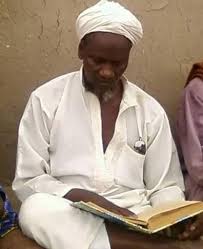

The Holy War of Amadou Koufa

In 2014 I went back to Mali to write about a jihadist warlord I thought was dead. Turned out he was very alive. I’m happy to see this story appear in Consequence.

In 2014 I went back to Mali to write about a jihadist warlord I thought was dead. Turned out he was very alive. I’m happy to see this story appear in Consequence.

Consequence: An International Literary Magazine Focusing on the Culture of War, 2019

Between Sin and Sin: Border Crossings

The very existence of the passport—a booklet of paper leaves bound by thread and staples—mystifies me. It retains authority rooted in 2,400 years of tradition. One of the earliest known uses of something like a passport dates to the year 450BC in the Book of Nehemiah of the Hebrew Bible. The story goes that the Persian King asked Nehemiah, a Jewish slave and trusted advisor, to go to Jerusalem in the province of Judah to establish himself as governor and rebuild the city. “If it pleases the king,” Nehemiah said, “let letters be given me to the governors of the province beyond the river, that they may grant me passage until I arrive in Judah.”

The very existence of the passport—a booklet of paper leaves bound by thread and staples—mystifies me. It retains authority rooted in 2,400 years of tradition. One of the earliest known uses of something like a passport dates to the year 450BC in the Book of Nehemiah of the Hebrew Bible. The story goes that the Persian King asked Nehemiah, a Jewish slave and trusted advisor, to go to Jerusalem in the province of Judah to establish himself as governor and rebuild the city. “If it pleases the king,” Nehemiah said, “let letters be given me to the governors of the province beyond the river, that they may grant me passage until I arrive in Judah.”

New Letters, Winter 2017/18

Welcome to Mali

On Mali’s border with Niger, in the early hours of July 3, 1986, a policeman in blue studied the passport of a man in herdsman’s clothes: white turban, brown vest, and dust stained djellaba that fell to his ankles. Satisfied, the policeman picked up a wooden stamp and leaned on the handle with the palm of his hand to press the date into a blank page. He brushed his fingers over the cover, presenting it back to the traveler like a communion host, pinched between thumbs and forefingers. He had a pudgy, relaxed face and smiled when the traveler spoke to him in Tamashek, language of the Berber Tuaregs. This was my first visit to Mali…

On Mali’s border with Niger, in the early hours of July 3, 1986, a policeman in blue studied the passport of a man in herdsman’s clothes: white turban, brown vest, and dust stained djellaba that fell to his ankles. Satisfied, the policeman picked up a wooden stamp and leaned on the handle with the palm of his hand to press the date into a blank page. He brushed his fingers over the cover, presenting it back to the traveler like a communion host, pinched between thumbs and forefingers. He had a pudgy, relaxed face and smiled when the traveler spoke to him in Tamashek, language of the Berber Tuaregs. This was my first visit to Mali…

—The New England Review, Fall 2016

Colonel Tandja’s Country FOURTH GENRE — Spring 2013 issue:

Not long ago, a man I used to know lost his job and went to prison in the space of a few hours. Months later and just as abruptly he returned home, charges dropped, with little explanation. His name is Mamadou Tandja. He was once a colonel in the army of Niger, a West Africa country more than twice the size of France and covered mostly by the Sahara…

Not long ago, a man I used to know lost his job and went to prison in the space of a few hours. Months later and just as abruptly he returned home, charges dropped, with little explanation. His name is Mamadou Tandja. He was once a colonel in the army of Niger, a West Africa country more than twice the size of France and covered mostly by the Sahara…

Al Qaeda Country – By Peter Chilson/Foreign Policy (Jan. 15, 2013)

In 1893, in West Africa’s upper Niger River basin — what is now central Mali — the French army achieved a victory that had eluded it for almost 50 years: the destruction of the jihadist Tukulor Empire, one of the last great challenges to France’s rule in the region. The Tukulor Empire’s first important conquest had come decades earlier, in the early 1850s, when its fanatical founder, El Hajj Umar Tall, led Koranic students and hardened soldiers to topple the Bambara kingdoms along the banks of the Niger. Umar imposed a strict brand of Islamic law, reportedly enslaving or killing tens of thousands of non-believers over a half century. He is said to have personally smashed to pieces captured idols, and once told a French officer he encountered at a well guarded fort to “Go back to your own country, accursed man.” Umar traveled widely, prophesying the end of French rule and preaching about the paradise that awaits those who die by jihad. Killed in the explosion of a gunpowder cache in 1864, it still took almost three decades for the French to wrest control over the middle and upper reaches of the Niger River, including Timbuktu and much of the desert to the north…

In 1893, in West Africa’s upper Niger River basin — what is now central Mali — the French army achieved a victory that had eluded it for almost 50 years: the destruction of the jihadist Tukulor Empire, one of the last great challenges to France’s rule in the region. The Tukulor Empire’s first important conquest had come decades earlier, in the early 1850s, when its fanatical founder, El Hajj Umar Tall, led Koranic students and hardened soldiers to topple the Bambara kingdoms along the banks of the Niger. Umar imposed a strict brand of Islamic law, reportedly enslaving or killing tens of thousands of non-believers over a half century. He is said to have personally smashed to pieces captured idols, and once told a French officer he encountered at a well guarded fort to “Go back to your own country, accursed man.” Umar traveled widely, prophesying the end of French rule and preaching about the paradise that awaits those who die by jihad. Killed in the explosion of a gunpowder cache in 1864, it still took almost three decades for the French to wrest control over the middle and upper reaches of the Niger River, including Timbuktu and much of the desert to the north…

Rebel Country – By Peter Chilson | Foreign Policy (Jan/Feb 2013 issue)

Bamako, a great sprawl of 2 million people on the Niger River, was in the grip of a gun battle. Soldiers of Mali’s new ruling junta, who wore the green berets of the regular army, had been in power all of five weeks when I arrived there late last April. Now they were fighting a countercoup attempt from the former presidential guard, an elite parachute regiment loyal to President Amadou Toumani Touré, the democratically elected leader who was deposed by junior army officers last March, when he had been weeks from retirement and elections to replace him. But by the time his guard — distinguished from other army units by its members’ bright red berets — made a move, he’d exiled himself to Senegal. They fought on without him…

Bamako, a great sprawl of 2 million people on the Niger River, was in the grip of a gun battle. Soldiers of Mali’s new ruling junta, who wore the green berets of the regular army, had been in power all of five weeks when I arrived there late last April. Now they were fighting a countercoup attempt from the former presidential guard, an elite parachute regiment loyal to President Amadou Toumani Touré, the democratically elected leader who was deposed by junior army officers last March, when he had been weeks from retirement and elections to replace him. But by the time his guard — distinguished from other army units by its members’ bright red berets — made a move, he’d exiled himself to Senegal. They fought on without him…

Waiting for the Rain – By Peter Chilson | Foreign Policy

In the impenetrable Dogon highlands of Mali, the storm of war is coming (Dec. 5, 2012)

In the impenetrable Dogon highlands of Mali, the storm of war is coming (Dec. 5, 2012)

OUAGADOUGOU, Burkina Faso — The town of Bandiagara, population 12,000, sits on a plateau of smooth sandstone bluffs, grass, acacia, and palm trees that ends at an astonishing complex of cliffs so high and abrupt that any of them on a dusty day can surprise a traveler as if a piece of the globe has suddenly broken away. Bandiagara’s dirt homes, shellacked with mud stucco, bear the red tinge of this land’s iron-rich soil, farmed for centuries by the Dogon people and roamed by Fulani and Tuareg herders. Homes stand along wide dirt streets useful for driving cattle and sheep to market, and at dawn and dusk buildings glow under a dusty sun. A few miles east of town, the cliffs drop 1,600 feet, grooving sharply in and out of the plateau along a 100-mile front, running from the south to the northeast like the edge of a saw. For over a thousand years, the cliffs have been a natural hideaway for one tribe or another, most recently the Dogon, a few hundred of whom came here 700 years ago to flee the Mali Empire’s embrace of Islam…

Lost City

After a week of wanton destruction, is the legendary city of Timbuktu finally coming to an end? (Foreign Policy July 10, 2012)

After a week of wanton destruction, is the legendary city of Timbuktu finally coming to an end? (Foreign Policy July 10, 2012)

Late in the afternoon of April 20, 1828, “just as the sun was touching the horizon,” as he later described it, a young Frenchman, barely 29, walked into Timbuktu disguised as an Arab, wearing long robes and a turban. René Caillié had begun his journey two years earlier in Senegal, and when the elation of arrival wore off, he looked around him at the streets of Timbuktu, a historic town he knewfor its “grandeur and wealth.” The city had been part of the Mali Empire, which was known for its trade in gold, salt, and spices, much of which passed through Timbuktu on its way north across the Sahara. Malian emperors built grand mosques in the city, and the Arab traveler Ibn Battuta visited in 1353, confirming Timbuktu’s importance to Mali and trans-Saharan trade. But Caillié was disappointed. “The sight before me did not answer my expectations,” he wrote in his memoirs. “The city presented, at first view, nothing but a mass of ill-looking houses, built of earth. Nothing was to be seen in all directions but immense plains of quicksand of a yellowish white colour … all nature wore a dreary aspect.”…

Limbo Land: A journey into the heart of Mali, a nation divided, with no good end in sight.

OUAHIGOUYA, Burkina Faso – In Koro, eastern Mali, nerves are raw in this town of 14,000 souls that live on a broad, arid plain near the border with Burkina Faso. A rumor rippled out from Koro’s marketplace early on a hot May afternoon, that rebel fighters from the north — Islamists or Tuareg nationalists, no one knew for sure — would attack the next day, Friday, the Muslim day of prayer. By Thursday night, when I went to interview Koro’s mayor, Soumaila Djinde, at his home, the rumor had become more specific: He told me that two local merchants had come to his office around 6 p.m., worried because they had heard that fighters from the Islamic Tuareg rebel group Ansar Dine — which participated in the fall of Timbuktu on April 1 in the rebellion that has split Mali in two — would visit Koro to show their strength and pray at the town’s large mosque. The mosque — a beautiful building of iron-rich, red-brown mud with high, pointed towers along each wall and thick ornate wooden doorways cut from giant baobab trees — was built hundreds of years ago by Dogon tribesmen from whom Djinde is descended… —Foreign Policy June 14, 2012

OUAHIGOUYA, Burkina Faso – In Koro, eastern Mali, nerves are raw in this town of 14,000 souls that live on a broad, arid plain near the border with Burkina Faso. A rumor rippled out from Koro’s marketplace early on a hot May afternoon, that rebel fighters from the north — Islamists or Tuareg nationalists, no one knew for sure — would attack the next day, Friday, the Muslim day of prayer. By Thursday night, when I went to interview Koro’s mayor, Soumaila Djinde, at his home, the rumor had become more specific: He told me that two local merchants had come to his office around 6 p.m., worried because they had heard that fighters from the Islamic Tuareg rebel group Ansar Dine — which participated in the fall of Timbuktu on April 1 in the rebellion that has split Mali in two — would visit Koro to show their strength and pray at the town’s large mosque. The mosque — a beautiful building of iron-rich, red-brown mud with high, pointed towers along each wall and thick ornate wooden doorways cut from giant baobab trees — was built hundreds of years ago by Dogon tribesmen from whom Djinde is descended… —Foreign Policy June 14, 2012

Bamako Days: Machine Guns and Mango Bombs

On Tuesday afternoon, May 1, 2012, after a sleepless night listening to distant machine gun chatter and popping of small arms from my hotel here in Bamako, capital of Mali, I was working in my room when a sharp “bang” rang out uncomfortably close to my window. Then came two more loud sounds. I got up and crept along the wall to the edge of the window where I peered out to see what was happening. There, just off the street about a hundred feet away, a young man hung from a rope in a densely branched mango tree, knocking the ripe fruit off with a metal pole. Mangoes fell—bang, bang, bang—on the corrugated iron roof of a shed. Humbled, I returned to my desk, thinking I need to get hold of myself… —Pulitzer Center for Crisis Reporting, May 2, 2012

On Tuesday afternoon, May 1, 2012, after a sleepless night listening to distant machine gun chatter and popping of small arms from my hotel here in Bamako, capital of Mali, I was working in my room when a sharp “bang” rang out uncomfortably close to my window. Then came two more loud sounds. I got up and crept along the wall to the edge of the window where I peered out to see what was happening. There, just off the street about a hundred feet away, a young man hung from a rope in a densely branched mango tree, knocking the ripe fruit off with a metal pole. Mangoes fell—bang, bang, bang—on the corrugated iron roof of a shed. Humbled, I returned to my desk, thinking I need to get hold of myself… —Pulitzer Center for Crisis Reporting, May 2, 2012

The Road from Abalak: heat, wind, dust, fear

Early on Christmas morning I stood with hundreds of people on a roadside in Abalak, a town in southern central Niger, West Africa, on the edge of the Sahara. I remember the peculiar fine dust, like talcum, that arrived on a cool wind and dyed the air a dirty gray. The harmattan, the Saharan winter wind, had been blowing from the northeast since November, hard enough to fill the sky with dust but not strongly enough to carry sand. Fine grit coated everything, including the fatigues of the soldiers who were running about, guns slung across their backs, shouting orders and directing traffic… —The American Scholar – June 22, 2002, and Best American Travel Writing 2003

Early on Christmas morning I stood with hundreds of people on a roadside in Abalak, a town in southern central Niger, West Africa, on the edge of the Sahara. I remember the peculiar fine dust, like talcum, that arrived on a cool wind and dyed the air a dirty gray. The harmattan, the Saharan winter wind, had been blowing from the northeast since November, hard enough to fill the sky with dust but not strongly enough to carry sand. Fine grit coated everything, including the fatigues of the soldiers who were running about, guns slung across their backs, shouting orders and directing traffic… —The American Scholar – June 22, 2002, and Best American Travel Writing 2003

Sporting Lives: Travels with My Brother

I gave up on God long ago. Left Colorado, too. Our parents are gone. And I’ve avoided chances to reunite with my siblings, share a holiday, the birth of a child. But Bert has forced the issue. If I wasn’t going to see the family, he’d come to me, like it or not. So, I’m at the Olympics in Vancouver with my brother on the chance this might be fun… — Ascent, November 2010, Best Sports Writing of 2010 citation in Best American Sports Writing.

I gave up on God long ago. Left Colorado, too. Our parents are gone. And I’ve avoided chances to reunite with my siblings, share a holiday, the birth of a child. But Bert has forced the issue. If I wasn’t going to see the family, he’d come to me, like it or not. So, I’m at the Olympics in Vancouver with my brother on the chance this might be fun… — Ascent, November 2010, Best Sports Writing of 2010 citation in Best American Sports Writing.

ROMANCING THE ARCHIVIST

I wanted to prove that West African borders were illusions, but first I had to get into Mali’s records, where the archivist tapped a pen on his desk, studying me. I wasn’t too worried, though he’d just accused me of spying in the national archives of Mali — a half desert West African country shaped like an hourglass broken at the ends. I did not fear deportation or worse, not in Mali, one of Africa’s new democracies. But I wasn’t sure if I was free to go or if I’d have to negotiate… —thesmartset.com, August 2008.

I wanted to prove that West African borders were illusions, but first I had to get into Mali’s records, where the archivist tapped a pen on his desk, studying me. I wasn’t too worried, though he’d just accused me of spying in the national archives of Mali — a half desert West African country shaped like an hourglass broken at the ends. I did not fear deportation or worse, not in Mali, one of Africa’s new democracies. But I wasn’t sure if I was free to go or if I’d have to negotiate… —thesmartset.com, August 2008.

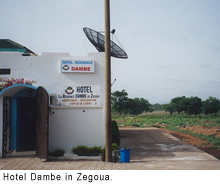

THE BORDER

I was in Cote d’Ivoire to interview a rebel commander of this war-torn country’s northern half. I was staying in Mali to the north. But I learned that in Africa, border distinctions aren’t always clear… — thesmartset.com, November 2007, Best American Travel Writing 2008.

I was in Cote d’Ivoire to interview a rebel commander of this war-torn country’s northern half. I was staying in Mali to the north. But I learned that in Africa, border distinctions aren’t always clear… — thesmartset.com, November 2007, Best American Travel Writing 2008.

In Large and Sunlit Land

Africa, where I’ve spent six ears of my life, and my adopted West are not so different. They exist under endless skies. They are mostly dry–in places very wet–lovely, harsh, and patient lands that have been ravaged by impatient people doing what they wanted… — High Country News, October 2007

Africa, where I’ve spent six ears of my life, and my adopted West are not so different. They exist under endless skies. They are mostly dry–in places very wet–lovely, harsh, and patient lands that have been ravaged by impatient people doing what they wanted… — High Country News, October 2007

Audubon: Cutting Edge

Every year, all kinds of wildlife, including many endangered species, are killed crossing America’s highways. Now biologists and land planners are teaming up to design ecofriendly roads that animals can traverse without having to risk life and limb… — Audubon Magazine, June 2003

Every year, all kinds of wildlife, including many endangered species, are killed crossing America’s highways. Now biologists and land planners are teaming up to design ecofriendly roads that animals can traverse without having to risk life and limb… — Audubon Magazine, June 2003

Homage to a difficult land: An African scientist returns home

Early on a windless afternoon–a brutal July day when the heat breaks 120 degrees–I’m sitting against a prosopis tree at longitude four degrees north and latitude 13 degrees west, a few miles east of the dwindling inland delta of the Niger River in Mali, West Africa. This point is about 200 miles southwest, as the river goes, of the ancient market and university town of Timbuktu on the edge of the Sahara, and a few yards from the white Toyota pickup that has arrived with supplies and water. The tree’s thorny branches reach out a few feet and bend to the ground, providing space and shade for me and three other men, including Oumar Badini, a soil scientist who sits beside me, holding a global positioning unit in his hand as he makes notes on a yellow pad… –Washington State University Magazine, Spring 2003

Early on a windless afternoon–a brutal July day when the heat breaks 120 degrees–I’m sitting against a prosopis tree at longitude four degrees north and latitude 13 degrees west, a few miles east of the dwindling inland delta of the Niger River in Mali, West Africa. This point is about 200 miles southwest, as the river goes, of the ancient market and university town of Timbuktu on the edge of the Sahara, and a few yards from the white Toyota pickup that has arrived with supplies and water. The tree’s thorny branches reach out a few feet and bend to the ground, providing space and shade for me and three other men, including Oumar Badini, a soil scientist who sits beside me, holding a global positioning unit in his hand as he makes notes on a yellow pad… –Washington State University Magazine, Spring 2003

Guilt and Malaria

I asked the boy his name to see if he was coherent, but he just stared up. Not at me, not at anything. He was a tall boy, thin, not strong, mostly bones. I held the back of his head in the palm of my hand because he kept knocking his skull against the floor, leaving a dim round sweat spot on the concrete… — Ascent, Fall 2001, Notable Essay citation in Best American Travel Writing 2002.

I asked the boy his name to see if he was coherent, but he just stared up. Not at me, not at anything. He was a tall boy, thin, not strong, mostly bones. I held the back of his head in the palm of my hand because he kept knocking his skull against the floor, leaving a dim round sweat spot on the concrete… — Ascent, Fall 2001, Notable Essay citation in Best American Travel Writing 2002.

Into the canyon: Fear and heat on foot

On the southeast rim of the Grand Canyon, at the South Kaibab trailhead, wind blows hard and cool at 4:20 a.m., even in July. I walk past the yellow sign with the fretting boy sitting on a rock under the sun. The sign reads, “Heat Kills!” A bus left five of us here moments ago, including a young Israeli man who says he’s traveling the country in a $500 station wagon and has dreamed of seeing the Grand Canyon since he was a boy. He pauses and offers a non sequitur: “I’ll just stay with you….” — High Country News, March 1998

On the southeast rim of the Grand Canyon, at the South Kaibab trailhead, wind blows hard and cool at 4:20 a.m., even in July. I walk past the yellow sign with the fretting boy sitting on a rock under the sun. The sign reads, “Heat Kills!” A bus left five of us here moments ago, including a young Israeli man who says he’s traveling the country in a $500 station wagon and has dreamed of seeing the Grand Canyon since he was a boy. He pauses and offers a non sequitur: “I’ll just stay with you….” — High Country News, March 1998

Listening to Mariko: Madness and Decay on an African Road

Niger’s first national highway, Route Nationale One, is historically rooted in greed and madness…haunted by men in uniform, and by blood… — The North American Review, July 1996

Niger’s first national highway, Route Nationale One, is historically rooted in greed and madness…haunted by men in uniform, and by blood… — The North American Review, July 1996

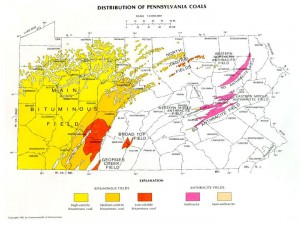

Teaching Power in a Land of Loss

Things get harder, weirder. Late October when the strip mines commence seasonal layoffs, liquor sales boom in small towns, as do suicides and family disputes, while the weather begins its games…Police say a woman drowned her baby in a toilet… — The North American Review, September 1995

Things get harder, weirder. Late October when the strip mines commence seasonal layoffs, liquor sales boom in small towns, as do suicides and family disputes, while the weather begins its games…Police say a woman drowned her baby in a toilet… — The North American Review, September 1995