The curator at the Sikasso Regional Museum here in the south of Mali tosses up his hands and falls on the floor of his office, flat on his back to demonstrate how the city of the same name, once the capital of the African kingdom of Kenedougou, fell to the French in 1898. He looks at me with his arms stretched out above his head. Then he sits up and brings his fists together. “They had this”: He mimes the rotating lever of the Gatling gun, “ta, ta, ta, ta, ta” and stops. “All we had were old guns or bows.” He mimed the pulling of a bowstring and made the swishing sound of the departing arrow. Back on his feet he brushed off his trousers. “The fight wasn’t fair and that’s why we have a monument to Samory. He was an enemy we could respect.”

Outside Sikasso, a city of 130,000, stands the point of our conversation—a lifelike statue of the warlord and Pan-African icon Samory Touré, who laid siege to Sikasso for fifteen months until August 1888. He died twelve years later, a prisoner of the French, not long after his capture, ending his campaign to push France off the continent and build a new African empire, one that if he’d succeeded—and he nearly did—might include all of what is now Mali and Burkina Faso, as well as Guinea and most if not all of Ivory Coast—a great chunk of West Africa. That likeness of Samory—mounted on a concrete platform atop the hill where he made his siege camp outside Sikasso—wears a white robe and black turban. He fingers prayer beads in one hand, clutching a Koran in the other while gazing upon the city he failed to take. The French were not a factor in the siege. They came later.

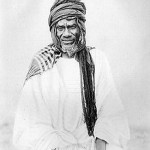

The statue is made of concrete and projects Samory in the image of a photograph taken shortly after his capture. A large portrait cropped from that photo hangs in the Sikasso museum. In the photo and on the statue, he looks thoughtful, face deeply lined, eyes a little menacing, a strange monument for a city and region that endured his scorched earth tactics. Tens of thousands died from starvation and disease or were butchered by his soldiers, themselves taken from conquered lands. He sold slaves to buy powder and weapons but did not formally pay or feed his army. Samory’s soldiers fed themselves on looting. A mile away, atop another hillock just outside Sikasso, stands the image of Samory’s general, Nankafali Camara, packing powder into a muzzle loaded rifle, his eyes wide and determined.

But Sikasso defied Samory, which, as the museum curator explains, is the point of the monument standing beyond what remains of the ancient wall that protected the city. Samory gave up the siege, assuming he could deal with Sikasso later. He moved on, taking lands to the east and south, in what is today Burkina Faso and Ivory Coast, until the French gradually wore down his armies and hunted him down, earning Samory his reputation as anti-colonial crusader. Not unlike the American Indian leader Chief Joseph of the Nez Perce, Samory struck his enemy and vanished, staying ahead of the French for a decade.

In 1898, months after Samory’s capture, the French took Sikasso, overwhelming the city’s archers and cavalry armed with rifles forged in the city’s iron works. The French used modern cannon and the Gatling gun, forerunner of the machine gun, a self-cooled weapon that fired multiple bullets per minute from several barrels mounted on a rotating cylinder activated by a hand lever, just as the museum curator showed me. Samory never breached Sikasso’s defensive wall of mud and rock, nine kilometers around, 12 feet high, and six feet thick. The French blew it to pieces, though sections of it remain to this day, mostly covered by thick brush. The architect of that wall, the king of Kenedougou, committed suicide (he ordered his own soldiers to execute him) rather than submit to French rule.